Executive and Line Managers in Indigenous corporations are a breed that has done it the hard way.

In our experience, they are people who have worked their way through more and more responsible positions in Government agencies or not-for-profit and Indigenous organisations, learning the ropes as their careers progressed.

Anything they know about managing people, project management, making decisions, analysing situations and organisational structures have been learned by doing, failing, and trying again.

If you contrast that with the general careers of commercial company management, these people studied a management-related topic in college or university like Accountancy, Management, Business, or also came through the ranks but in the professional trades like Engineering. If they actually worked through the ranks, once identified as management material, they would almost certainly have been sent to a management course.

This is a very different way of gaining knowledge and expertise in that strange skill called management.

Indigenous corporations rarely have the resources to identify promising young people and put them into a career path, nor do they have the resources to allow people time off to study a formal course, let alone pay for it. So managers in Indigenous corporations tend to be more mature and have little opportunity for formal training in management skills.

This is changing to some extent with the better resources larger Indigenous organisations, such as the more well-resourced Native Title Prescribed Bodies Corporate. They are starting to employ more formally trained and experienced management as they become more able to compete with commercial companies in terms of market-rate salaries.

However, for every properly resourced PBC, there are a dozen of small PBC's with a $50,000 a year grant as their sole income to develop administration. For every well-resourced and progressive Indigenous organisation, there are 20 small ones that struggle to find the right people with the right management skills.

But management is a skill that can be gained through training or through keen observation and experience.

Do not underestimate the self-made, well-experienced manager.

However, all management do need access to some management tools to help them in their work. Many people are well aware of some of these already - for example, the SWOT Analysis tool to help identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats, and in so doing organise categories of actions and prioritise them in order to build up the strengths of the organisation.

There are many of these simple tools - ways or processes to take information, analyse that information, think about it in a different way, and find solutions.

These tools can help you to organise your thinking about problems and solutions, communicate better, be more clear about instructions and delegation. They can help you to analyse different issues within the organisation. They can help you to generate and develop the most appropriate solutions to problems, They can help you to implement decisions and actions and to measure and monitor results.

Here are a few that management may find useful.

General Analysis

All managers have to solve problems. The use of The Problem Solving Model helps you to reframe the problem in such a way that you can address the problem in a consistent way.

The Problem Solving Model is a six-step process:-

- Define the improvement opportunity - frame the issue, not as a problem that can shut down thinking, but as a positive opportunity to improve and get better. Asking "Why are people so slow in their work?" cuts out a lot of innovative thinking. Asking "How can we shorten processes to get better productivity?" fires off suggestions out of the box.

- Identify the root cause. Collect information about why the situation is happening, then analyse the information always asking "why?" until you go back to the root cause. This will allow you to restate the improvement opportunity to focus on improving the root cause.

- Identify possible solutions - gather as many options as possible and don't discard any because they "sound stupid". When we were all using Nokia mobile phones, having a computer in your pocket sounded stupid.

- Select the best solution - assess all the ideas fairly, but especially assess their effectiveness to make the improvement desired and choose the best for the situation - the best that is appropriate because "the very best" may not be accessible or affordable to you.

- Implement and then test the solution. Plan it out, then observe, monitor and evaluate. Make changes if necessary, and don;t forget to call it a failure and go to the next best solution.

- Keep monitoring performance, and when appropriate standardise it across the organisation.

Analysing Issues

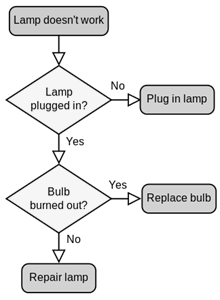

Most of us know about mindmaps to help us identify connections, but what about Flowcharts?

Flowcharts are simple graphic representations of how things work, what steps follow which and where bottlenecks occur. They can help you identify problems with processes as well as make obvious solutions to problems.

Flowchart

When you construct your flowchart:

- Define the parameters - where does it start, and where does it end, and what is the intended outcome at the end?

- Use simple consistent symbols like square for descriptions or actions, diamond shapes for decisions, and so on.

- Just like most processes go one way, be consistent about the flow of one action after another, in the right order.

- If there is a feedback loop, make sure there is an escape path. For example, a decision about the quality of output may depend on the process meeting a standard approval. The process may go into a feedback loop because it is never good enough to meet the standard approval measures. You can include an exit where if it fails 10 times, it has to start again but under better supervision.

Prioritisation of Work

Overwhelm is always present in Indigenous organisations, simply because resources is never enough to do all the work efficiently and on time.

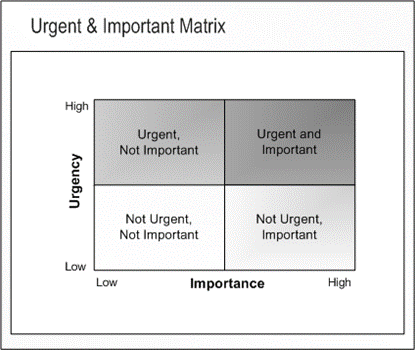

The Urgent/Important Matrix is a prioritisation tool to help you decide what work should be prioritised, whether personal tasks or program activities and consistent use will help you to organise ongoing priorities.

Using the Urgent/Important Matrix:

Urgent Important

- List the tasks, activities or actions that are on your list to do.

- On a scale of 1 to 10 where 10 is the most Urgent, score each task.

- On a scale of 1 to 10 where 10 is the most Important, score each task.

- Each task will now have two scores - plot them into the matrix.

- Tasks that are not urgent and not important should be ignored, avoided, or given away.

- Tasks that are urgent but not important should be delegated.

- Tasks that are urgent and important should be done now.

- Tasks that are not urgent but important should be scheduled.

Using The Urgent/Important Matrix over time, and as you avoid, delegate or complete the other tasks, you should be spending most of your time on Not Urgent But Important tasks so that you are ahead of the curve in dealing with strategically important things.

55 Really Useful Management Tools

These are just some of the management tools that you can use in your everyday work to help you manage more efficiently and productively.

Our Managing Director and founder of OTS Management has written a book called "The Management Toolbox" that compiles 55 really useful management tools in one book.

It is organised by the purpose of the management tool, but also indexed alphabetically, and according to the task at hand.

It is available for $19.97 from the publisher here.

As a manager in an Indigenous organisation, it is a useful companion book to have on your shelf.

As an Indigenous corporation trying to support the work of its managers, why not buy several copies to distribute to them?

If you would like any further information about how we can help you to develop your management talent, send us an email to or call 08 9242 2085.